A Practical Guide to Uncertainty Estimation Methods for Large Language Models

As large language models (LLMs) enter safety-critical domains, understanding and managing their uncertainty is essential for trustworthy deployment. This post explores different methods for uncertainty quantification (UQ) — from sampling and calibration to self-reflection and concept-level analysis — and discusses how these techniques may help make AI systems more reliable, transparent, and safe in real-world applications.

Executive summary

As Large Language Models (LLMs) are increasingly integrated into high-stakes, safety-critical domains, such as the maritime, energy, and industrial sectors, the ability to reliably measure their uncertainty is becoming a fundamental requirement for safe deployment. Unlike traditional software, LLMs can generate outputs that are plausible-sounding but factually incorrect or based on incomplete knowledge. This tendency towards ‘hallucination’ makes it essential to quantify models’ confidence in their own responses to prevent potentially severe consequences.

The unique challenges posed by LLMs, such as their open-ended outputs, the ambiguity of user prompts, and their capacity to invent credible but false information, render traditional software validation and uncertainty quantification (UQ) methods insufficient on their own.

Sources of Uncertainty and Key Technical Approaches

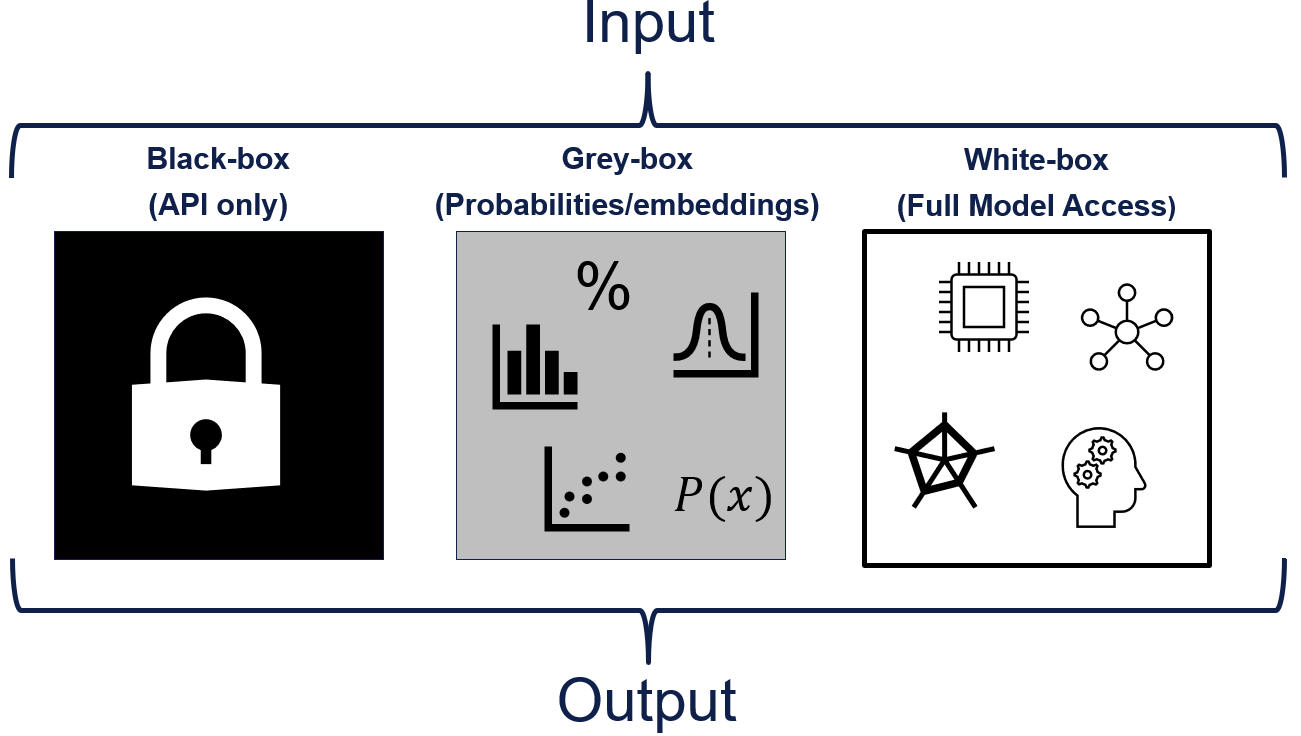

Uncertainty in LLMs stems from multiple sources, including models’ internal architecture (model-intrinsic uncertainty), gaps in their knowledge base (content uncertainty), and ambiguity in user prompts (contextual uncertainty). To address this complex landscape, a diverse range of UQ methods have emerged, categorized by the level of model access required:

- Black-box methods (API access only): These approaches work only with model input and output.

- Grey-box methods (access to probabilities/embeddings): These leverage deeper model outputs.

- White-box methods (full model access): These involve direct modification or deep inspection of the model.

Choosing the Right Approach and the Path Forward

The selection of UQ methods is often a trade-off between fidelity, computational cost, and implementation complexity, dictated by the level of model access available and the specific application's risk profile. The future of safe AI deployment depends on advancing the robustness, reliability, and efficiency of these UQ techniques. Progress requires a collaborative effort across research, industry, and regulation. Key priorities include developing robust UQ methods, establishing standardized benchmarks for evaluation, and creating industry-specific guidelines for implementation.

Ultimately, achieving trustworthy AI is not merely a technical challenge but demands a cultural shift toward comprehensive, lifecycle-based assurance, where cutting-edge innovation is paired with rigorous, independent validation to ensure these powerful systems can be deployed safely and confidently in the real world.

Why do we need UQ for LLMs?

LLMs have achieved remarkable capabilities across diverse applications, from processing technical documentation to supporting complex decision-making in fields like healthcare, engineering, and financial services. However, their increasing deployment in high-stakes environments brings a critical challenge: How can we reliably tell when these models are uncertain about their outputs?

Unlike traditional software systems that operate with deterministic logic and clear failure modes, LLMs present unique challenges that complicate their deployment in critical applications. Consider a medical diagnosis support system analysing patient records. While the system might generate clinically coherent and plausible-sounding recommendations, quantifying its confidence level becomes as critical as the suggestion itself. A misplaced sense of certainty could lead to overlooked conditions or unnecessary treatments, potentially compromising patient safety.

Several factors make uncertainty quantification particularly challenging for LLMs:

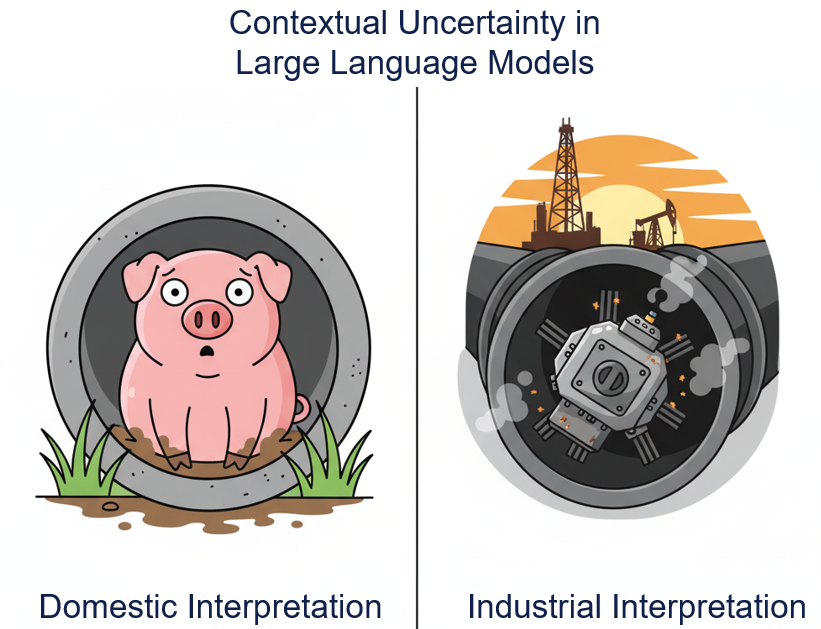

First, LLMs typically produce open-ended context-sensitive outputs, which complicates uncertainty estimation. Unlike classification tasks with a finite set of possible outcomes, LLMs can generate a wide variety of plausible responses to the same input, which may all be valid depending on the context. For example, consider the prompt “What should I do if my pig is stuck in a pipe?” In the oil and gas industry, this refers to an issue involving pipeline inspection gauges (PIGs), while a general-purpose LLM might interpret this literally as an animal stuck in a pipe. These kinds of ambiguities challenge the definition of “correct” and make it difficult to assess when the model is uncertain due to lack of knowledge vs. contextual misalignment.

Figure 1: An LLM might get the context wrong.

Second, LLMs can generate highly plausible output even when operating outside their training distribution or knowledge boundaries. Their ability to recombine information in novel ways makes it hard to discern whether a response is genuinely informed or merely a confident-sounding hallucination. This is particularly risky in technical domains where precision is crucial. For example, if a model invents a scientific explanation or formula that appears credible but is entirely fabricated, the consequences could be severe.

Traditional approaches to software validation, such as unit testing and formal verification, become inadequate when dealing with systems that can produce infinite variations of linguistically correct but potentially factually incorrect responses. Meanwhile, conventional uncertainty methods developed for neural networks – such as Bayesian neural networks (BNNs), Monte Carlo dropout, and deep ensembles – provide a foundation but have limitations due to the unique characteristics of LLMs 1.

Specifically challenges arise from:

- The scale and complexity of model architectures

- Temporal evolution of knowledge and potential staleness

- Interaction between different types of uncertainty (e.g. uncertainty about facts versus interpretation)

- The difficulty of maintaining calibration across diverse domains and tasks

While these approaches remain valuable as baseline techniques or components within hybrid strategies, they are generally insufficient on their own to capture the full scope of uncertainty in LLMs.

Recent developments have highlighted both opportunities and risks in LLM uncertainty quantification. For example, researchers have demonstrated that LLM uncertainty measures can be manipulated through backdoor attacks without affecting primary outputs 2, raising concerns about their reliability in critical applications. Such vulnerabilities emphasize the importance of developing robust uncertainty quantification methods that can withstand potential manipulation while providing reliable confidence measures.

As LLMs become increasingly integrated into high-stakes environments, reliable uncertainty quantification becomes not just a technical challenge but a practical necessity. The following sections explore various approaches to measuring and managing uncertainty in these models, from traditional statistical methods to cutting-edge techniques specifically designed for their unique characteristics.

Sources and Manifestations of Uncertainty in LLM Outputs

Before diving into the technical approaches, it is essential to understand the different types of uncertainty we encounter in LLM applications. Traditional machine learning systems typically deal with well-defined uncertainty in well-bounded classification or regression tasks. LLMs, however, present a more complex and nuanced uncertainty landscape that requires careful consideration.

Model-Intrinsic Uncertainty:

One major source of uncertainty originates from the architecture and training processes of LLMs. Pre-trained LLMs consist of billions of parameters trained on massive and diverse text corpora, resulting in complex internal representations that encode associations and knowledge across many domains. These internal states enable models to assign probabilities to a wide range of plausible responses. When generating output, decoding strategies such as sampling or temperature scaling introduce controlled randomness, which can lead to different, but still viable, answers to the same prompt. For instance, when asked ‘What inspection methods are recommended for detecting corrosion in offshore pipelines?’ , the model might suggest ultrasonic testing, magnetic flux leakage, or visual inspection, depending on which part of the output distribution is sampled. Each method is valid in different scenarios, but without a mechanism to express uncertainty or ask clarifying questions, the model’s response might omit crucial context, such as environmental conditions or regulatory constraints.

Content and Contextual Uncertainty:

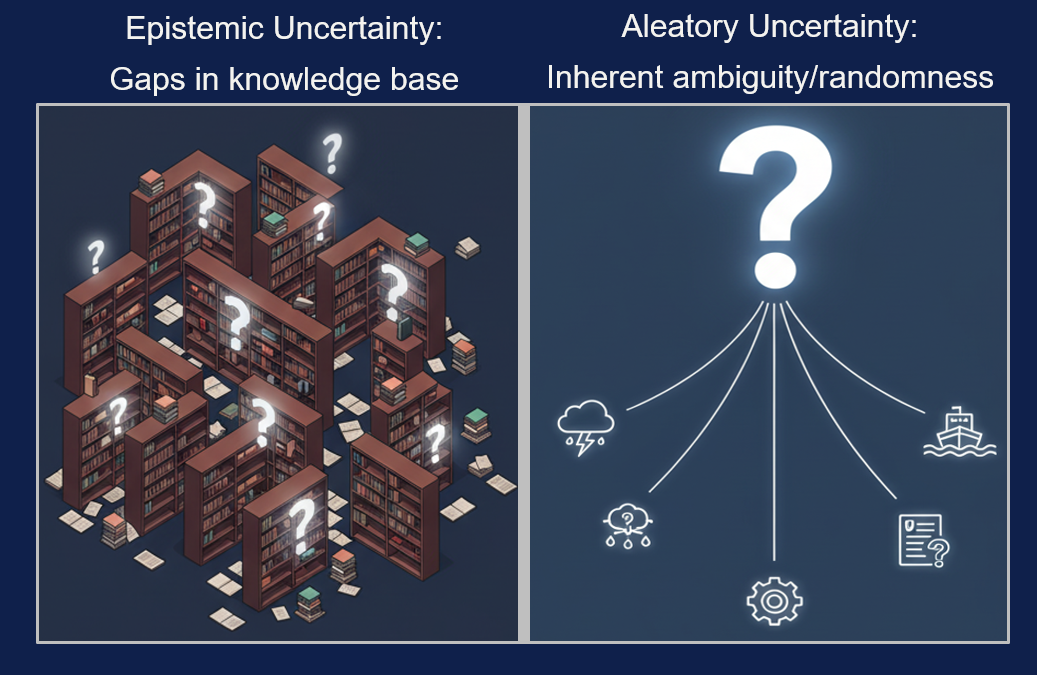

Content uncertainty occurs when a model responds to domain-specific questions outside its knowledge base or training data’s temporal cutoff. For example, when asked ‘ What are the 2025 emission standards for maritime shipping? ’, an LLM trained only on data up to 2023 may still generate a plausible-sounding response, despite lacking access to the relevant up-to-date information. This reflects an epistemic uncertainty – a gap in the model’s knowledge which, in theory, could be reduced with updated data or additional training.

In contrast, contextual uncertainty arises when a prompt is open to multiple interpretations. For example, a question like ‘ Is this pump operating safely?’ may depend on factors not explicitly stated, such as operating conditions, definitions of safety, or other system-specific information. Even with relevant training data, this kind of aleatory uncertainty represents the inherent ambiguity or randomness in the task or data.

Figure 2: Epistemic and aleatory uncertainty.

Implications and Mitigation Strategies:

Together, these forms of uncertainty shape how LLMs handle unknowns. In high-stakes applications, overlooking such ambiguities and uncertainties can lead to serious consequences. Recent work 5 has begun to formalize ways of distinguishing between these types of uncertainty. This, in turn, supports more targeted mitigation strategies, such as using uncertainty-aware prompting to encourage more cautious or qualified responses, applying ensemble methods to identify disagreement across outputs, or introducing fallback mechanisms that route uncertain cases to human experts. Some of the common approaches for quantifying and managing uncertainty are explored in more detail in the following sections.

Technical Approaches to Uncertainty Quantification

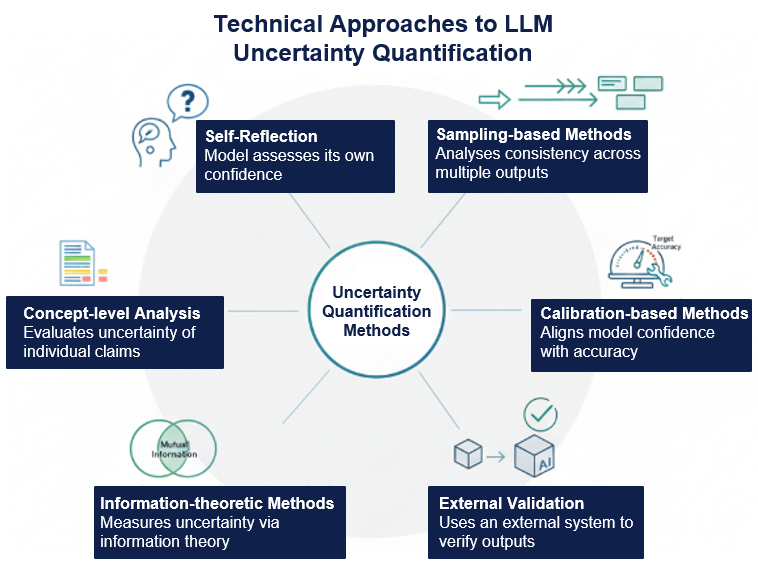

Recent research has introduced a variety of approaches for quantifying uncertainty in LLMs, each with its distinct strengths and limitations, and each addressing different aspects of the uncertainty challenge. Below, we summarize some of the key categories of technical approaches.

Figure 3: Overview of technical approaches to uncertainty quantification.

Self-Reflection and Verbalization

As LLMs grow more capable, methods are being developed to enable them to express uncertainty in ways that align more closely with human communication. Self-reflection and verbalization approaches aim to convert internal model confidence into natural language statements that are both interpretable and well-calibrated.

One such method is Pure Self-Reflection, where the model assesses its own output. While early approaches relied on direct confidence ratings, recent frameworks like Think Twice Before Trusting 4 enhance this by introducing a structured reasoning step prior to expressing confidence. This discourages overconfidence by grounding estimates in a justification process. Another variant, Calibrated Self-Expression 5, fine-tunes models to generate verbalized uncertainty statements aligned with actual performance, effectively mapping internal confidence scores to natural language. Despite their promise, these methods also face challenges: self-reflection can be computationally demanding due to repeated inference steps, while calibrated verbalization depends heavily on training data quality and generalization.

Sampling-based Methods

Sampling-based approaches estimate uncertainty by generating multiple responses to the same prompt and analysing their consistency. If the model produces very different answers, this suggests higher uncertainty. One basic way of doing this involves asking the same question multiple times with slight variations in prompts, or by using temperature scaling to introduce randomness in how the model samples probable outputs during the generation process.

Recent work has advanced these techniques with more sophisticated approaches, beyond simple agreement checking. The Semantically Diverse Language Generation (SDLG) framework 6 uses importance sampling with semantic steering to efficiently generate diverse yet probable responses. This method essentially guides the model to explore different reasoning paths explicitly, by prompting it to answer from different perspectives. This encourages the model to produce a variety of plausible but different answers, helping to better capture the range of uncertainty.

Another approach 7 proposes analysing the relationships between responses through graph-theoretic measures. This involves grouping similar answers into clusters (based on their embeddings) and representing each answer as a node in a graph. By measuring how connected or spread out these nodes are, this method goes beyond simply counting how many answers differ, to also analysing the structure and connections between responses to better capture their diversity.

While effective, these sampling-based methods also present certain challenges. First, evaluating uncertainty in open-ended generation tasks is fundamentally difficult due to the lack of clear evaluation metrics and ground truth labels. Second, these methods often require multiple model calls, which can be impractical due to computational constraints. Third, uncertainty in generation (how consistently a model responds) must be distinguished from factual uncertainty (whether the model's knowledge is reliable). As sampling methods primarily address the former, they do not fully reflect the uncertainty of the output

Concept-Level Analysis

As LLMs increasingly generate longer, more complex outputs, researchers are developing methods to analyse uncertainty at a more granular level than treating the entire response as a single unit. This concept-level approach breaks down responses into meaningful components, such as facts, claims, or entities, that can be evaluated independently.

One key challenge these methods address is the ‘information entanglement issue’, where different parts of a response may have varying levels of uncertainty. For instance, in a biographical response, fundamental facts such as birth date may be more certain than claims about lesser-known achievements. Recent work has introduced frameworks to tackle this challenge. The Concept-Level Uncertainty Estimation (CLUE) framework 8 extracts high-level concepts from LLM outputs and evaluates their uncertainty independently. For long-form text specifically, the Long-text Uncertainty Quantification (LUQ) framework 9 introduces specialized techniques for measuring uncertainty in extended generations, including sentence-level consistency assessment.

These approaches offer practitioners more nuanced methods for understanding where and how their LLMs express uncertainty, enabling better quality control and more selective response strategies. Rather than simply flagging an entire response as uncertain, they can identify which specific claims or components call for closer inspection. This enables more targeted quality control, human review, and response filtering. However, concept-level analysis comes with its own challenges. These methods typically require significant computational overhead, as they depend on additional models for concept extraction and scoring. Additionally, there is no universal agreement on what constitutes a ‘concept’ or how granular the breakdown should be. Despite these limitations, concept-level uncertainty analysis represents an important step towards more precise and actionable uncertainty quantification in LLM outputs.

Calibration-based Methods

Calibration is about aligning a model’s confidence with its actual accuracy. In other words, if a model is 90 percent confident about an answer, it should be correct 90 percent of the time. Well-calibrated models help users know when to trust an output and when to be cautious.

Recent work has introduced several approaches to calibrating uncertainty in LLMs. These methods can be broadly divided into two categories: post-hoc calibration (applied after the model is trained) and calibrated fine-tuning (applied during training).

Post-hoc Calibration:

These methods adjust model confidence after the LLM has been trained. This is especially useful when only black-box API access is available (i.e. when we cannot modify the model itself). APRICOT 10 is one such method, which uses an auxiliary model to predict how confident the LLM is likely to be, based on its input and output. This auxiliary model is trained to match the LLM's confidence with how often it is actually correct. Another approach by 11 uses conformal prediction techniques. Without needing access to model internals, it looks at how often similar outputs occur across multiple runs, and how semantically close they are. This helps estimate uncertainty based on the frequency and similarity of responses. These post-hoc methods are flexible and API-friendly but often involve numerous model calls, potentially making them resource-intensive.

Calibrated Fine-Tuning:

When we do have access to model internals, calibration can be built directly into the training process. UQ4CT 12 is one such example, which uses a mixture-of-experts architecture. In this setup, different parts of the model specialize in capturing uncertainty across different regions of the input space, enabling the model to generate more reliable confidence estimates. While this approach can improve calibration from the ground up, it also requires significantly more computational resources and full model access during training.

Challenges and Limitations

Despite recent progress, calibration remains a tough problem, especially for open-ended tasks like text generation or reasoning, where there is no single ‘correct’ answer. Most calibration methods work best for structured tasks like multiple-choice questions or fact-based QA. Moreover, both post-hoc and fine-tuning methods come with trade-offs. Post-hoc calibration may be easier to apply but less precise, while fine-tuning offers deeper integration but demands more computational resources. Overall, calibration is a promising way to make LLMs more trustworthy, but we still need more robust techniques for handling the complexity and subjectivity of real-world language tasks.

Information-Theoretic Methods

Information-theoretic and Bayesian frameworks provide more rigorous theoretical foundations for quantifying uncertainty in LLMs. One such method focuses on mutual information, which quantifies how much knowing one variable reduces uncertainty about another. Recent work by 3 applies this concept by examining how much information a model’s response contains about earlier parts of the prompt. For example, if the model’s output varies significantly based on slight changes in the phrasing of a question, this suggests a higher degree of uncertainty. This tendency can be quantified through iterative prompting – that is, repeatedly asking the same question in slightly different ways and analysing the consistency of the model’s answers using mutual information metrics.

Another promising direction frames uncertainty quantification through Bayesian decision theory 13. Under this framework, uncertainty is defined by a model's ability to maximize expected utility, measured through similarity functions between generated responses and ideal or reference answers. This approach is particularly valuable for open-ended generation tasks, like summarization or translation, where there might be multiple valid responses.

While these information-theoretic approaches provide a strong theoretical foundation, they are constrained by practical limitations. The methods typically require multiple forward passes through the LLM, increasing computational costs. Additionally, they depend on careful design of prompt perturbations and on assumptions and calibrations about how variation in responses reflects uncertainty. Despite these constraints, information-theoretic methods represent a significant advance over simpler heuristic approaches, such as response variability or voting-based agreement, offering practitioners more reliable uncertainty estimates when the application requirements justify the additional implementation complexity.

External Validation Approaches

An emerging approach to quantifying uncertainty in LLMs involves using external validation mechanisms. These approaches analyse both model outputs and internal states to assess uncertainty, aiming to distinguish whether it arises from limitations in the model’s knowledge or from inherent ambiguity in the task.

Recent work by 14 demonstrates how larger language models can serve as validators for smaller ones. When a smaller model expresses uncertainty but a larger model is confident, this suggests that the uncertainty stems from limitations in the smaller model’s knowledge. Conversely, when both models express uncertainty, it likely reflects inherent ambiguity in the task itself.

A different approach by 15 involves building a separate machine learning model that learns to predict an LLM’s uncertainty based on both its intermediate activations and generated outputs. The process involves collecting many examples of LLM responses along with labels indicating how confident or uncertain those responses are (often based on human judgement or external measures). This supervised model then learns patterns in the LLM’s internal computations that correspond to uncertainty. Once trained, the system can estimate uncertainty more accurately than it would using just the LLM’s raw confidence. This approach demonstrates that the hidden states of an LLM contain meaningful uncertainty information that can be extracted and leveraged through supervised learning, essentially serving as an ‘uncertainty interpreter’.

However, these validation mechanisms also have inherent limitations. No validator is perfect, and these methods work best when both the model and validator have been exposed to similar training data, as out-of-distribution examples can lead to misleading uncertainty estimates. Additionally, practical implementation requires significant computational resources. Despite these constraints, external validation approaches provide valuable tools for identifying different types of uncertainty.

Choosing the right approach

The choice of uncertainty quantification method often depends on the level of model access available and the practical constraints of the application. Different approaches offer trade-offs in terms of fidelity, computational cost, interpretability, and ease of implementation.

In black-box scenarios, where only the model’s inputs and outputs are accessible (such as through an API), methods like self-reflection, sampling-based approaches, and output-based calibration techniques are viable options. These methods do not require access to the LLM’s internal representations or probabilities.

In grey-box scenarios, where access to model probabilities and embeddings is available, additional techniques become feasible, such as enhanced sampling methods, mutual information-based measures, and probability-based calibration.

Full white-box access, where model weights and internal states are available, enables the most sophisticated approaches. These include training supervised models to predict uncertainty using internal features such as activations or attention patterns (e.g. 15). Other methods include architectural modifications to explicitly represent uncertainty, such as Bayesian neural networks that treat weights as distributions, or using Monte Carlo dropout at inference time to simulate model uncertainty.

Figure 4: Different approaches to uncertainty quantification require different levels of model access.

Each approach offers different trade-offs between accuracy, computational cost, and implementation complexity. Ultimately, the best choice depends on the specific application, available resources, and how essential reliable uncertainty estimation is for the use case.

To provide a more comprehensive overview, we include a summary table below highlighting some of the key approaches, including example applications, pros and cons, and references to relevant research for further details.

| Access Level | Approach Type | Examples | Pros | Cons | Typical Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black-box | Sampling-based | Temperature sampling, prompt perturbation, Semantically Diverse Language Generation (SDLG)6 | Intuitive, task-agnostic | Requires multiple model calls; computationally expensive | Text generation, summarization |

| Black-box | Self-reflection | ‘Think Twice Before Trusting’ framework 4; | Low overhead; model-native | Sensitive to prompt design; may still produce overconfident judgments | Question answering, complex reasoning task |

| Black-box | Output-based calibration | Conformal prediction 11; confidence scaling | Lightweight; improves trust | Needs calibration data; limited for open-ended tasks | Classification (incl. sentiment, topic), multiple-choice QA |

| Grey-box | Enhanced sampling | Entropy filtering 16; mutual-information prompting 17 | More granular than basic sampling | Still compute-intensive; implementation complexity | Reranking generated outputs (e.g. translation, code synthesis), |

| Grey-box | Mutual information-based | Iterative prompting 3 | Strong theoretical foundation | Compute-intensive (multiple forward passes), sensitive to prompt design and perturbation choices | Summarization, translation, reranking generated text |

| Grey-box | Probability-based calibration | Token-level entropy 18; softmax thresholds 19 | Fine-grained uncertainty signals | Misleading on out-of-distribution data | Token-level tasks (e.g. translation, summarization), structured QA |

| White-box | Supervised on activations | Train classifier on hidden states 15 | Leverages rich internal signals | Requires labelled uncertainty data; intermediate access needed | High-stakes QA (e.g. medical/legal advice), automated output validation |

| White-box | Feature-based supervised training | Add auxiliary heads for uncertainty prediction 20. | Highly accurate; customizable | Requires full model retraining and labelled data | Custom LLM pipelines, RLHF-based calibration, domain-adapted UQ |

| White-box | Architecture modifications | Monte Carlo Dropout (MCD) , Deep Ensembles, Bayesian Neural Networks. 21 | Theoretically grounded, strong baseline method | Computationally expensive, high implementation complexity | Research prototyping, safety-critical deployment |

Next Steps in LLM Uncertainty Estimation

As LLM applications continue to expand into domains such as healthcare, finance, and engineering, the need for more robust and reliable uncertainty-quantification (UQ) methods becomes paramount. Several key areas require focused development to bridge the gap between theoretical understanding and practical implementation.

Research Priorities

Current UQ methods require significant advancement in robustness and reliability. The development of manipulation-resistant techniques that can withstand adversarial attacks while maintaining reliability is important. This must be coupled with adaptive calibration methods that remain accurate across different domains and use cases. Additionally, efficient real-time uncertainty estimation algorithms need to be designed to balance accuracy with computational cost, enabling systems to flag uncertainty ‘on the fly’ without compromising throughput.

To measure progress, standardized evaluation frameworks are crucial for comparing and validating different UQ approaches. This includes comprehensive benchmark suites that test UQ methods across diverse scenarios and failure modes, as well as domain-specific test sets that capture unique challenges in high-stakes fields. The field needs new metrics that can effectively measure uncertainty in open-ended generation tasks.

Industry Implementation

To enable widespread adoption, translating research advances into production, the field needs clear standards and guidelines. This includes developing industry-specific best practices for implementing UQ for LLMs in different applications, and creating certification procedures that can verify the reliability of UQ methods. Organizations need clear integration guidelines to incorporate UQ into existing risk management frameworks.

Practical implementation requires robust tooling, including real-time monitoring systems that can track uncertainty across different types of LLM output. Integration frameworks must allow smooth incorporation of UQ methods into existing workflows, while debugging and validation tools should help practitioners identify and address errors in uncertainty estimates to ensure their accuracy and reliability.

Bridging Research and Practice

The advancement of LLM uncertainty quantification requires close collaboration between research, industry, and regulators. This includes developing open-source implementations, reference architectures, and educational resources for practitioners. Joint research projects between academia and industry can address real-world challenges using shared datasets and benchmarks that reflect actual deployment scenarios. Engagement with regulatory bodies is essential for developing appropriate standards and frameworks for auditing UQ for LLM implementation. This collaboration will help establish guidelines for responsible deployment in regulated industries.

Conclusion: A Call to Action for Safe AI Deployment

The ability to accurately assess and communicate uncertainty is one of the most urgent challenges in AI safety today. The field continues to evolve rapidly, with new methods and frameworks emerging regularly. As these systems are increasingly deployed and integrated in high-stakes environments, the consequences of failures also become more severe . The work being done to develop and validate UQ methods will form the foundation for the safe and reliable AI systems of the future.

Success in this endeavor requires continued collaboration among researchers, industry practitioners, and regulatory bodies. However, the path to unlocking the full value of AI in critical sectors is not through a technology-only approach. It requires a dedicated partnership between the innovators developing these powerful models and the assurance experts who can provide the independent, rigorous validation needed to ensure they are safe for real-world deployment. The call to action for industry leaders is clear: move beyond ad-hoc technical solutions and embrace a culture of comprehensive, lifecycle-based assurance. By combining cutting-edge technology with principled assurance, we can confidently navigate the new frontier of AI risk to build safe, robust and trustworthy AI systems.

References

-

Abdar, Moloud, et al. "A review of uncertainty quantification in deep learning: Techniques, applications and challenges." Information fusion 76 (2021): 243-297. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1566253521001081 ↩

-

Zeng et al. 2024. Uncertainty is Fragile: Manipulating Uncertainty in Large Language Models. https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.11282 ↩

-

Yadkori et al. 2024. To Believe or Not to Believe Your LLM. https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.02543 ↩↩

-

Li et al. 2024. Think Twice Before Trusting: Self-Detection for Large Language Models through Comprehensive Answer Reflection. https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.09972 ↩↩

-

Chaudhry et al. 2024. Finetuning Language Models to Emit Linguistic Expressions of Uncertainty. https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.12180 ↩↩

-

Aichberg et al. 2024. Semantically Diverse Language Generation for Uncertainty Estimation in Language Models. https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.04306 ↩↩

-

Lin et al. 2024. Generating with confidence uncertainty quantification for black box large language models. https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.19187 ↩

-

Wang et al. 2024. CLUE Concept Level Uncertainty Estimation for Large Language Models. https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.03021 ↩

-

Zhang et al. 2024. LUQ Long text Uncertainty Quantification for LLMs. https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.20279 ↩

-

Ulmer et al. 2024. Calibrating Large Language Models Using Their Generations Only. https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.05973 ↩

-

Su et al. 2024. API is Enough: Conformal Prediction for Large Language Models without Logit Access. https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.01216 ↩↩

-

Niu et al. 2024. Functional Level Uncertainty Quantification for Calibrated Fine Tuning on LLMs. https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.06431 ↩

-

Wang et al. 2024. On Subjective Uncertainty Quantification and Calibration in Natural Language Generation. https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.05213 ↩

-

Ahdritz et al. 2024. Distinguishing the Knowable from the Unknowable with Language Models. https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.03563 ↩

-

Liu et al. 2024. Uncertainty Estimation and Quantification for LLMs A Simple Supervised Approach. https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.15993 ↩↩↩

-

Kuhn et al. 2023. Semantic Uncertainty: Linguistic Invariances for Uncertainty Estimation in Natural Language Generation. https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.09664 ↩

-

van der Poel et al., 2022. Mutual Information Alleviates Hallucinations in Abstractive Summarization. https://arxiv.org/abs/2210.13210 ↩

-

Zhang et al. 2025. Token-Level Uncertainty Estimation for Large Language Model Reasoning. https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.11737 ↩

-

Możejko et al. 2018. Inhibited Softmax for Uncertainty Estimation in Neural Networks. https://arxiv.org/abs/1810.01861 ↩

-

Shelmanov et al., 2025. A Head to Predict and a Head to Question: Pre-trained Uncertainty Quantification Heads for Hallucination Detection in LLM Outputs. https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.08200 ↩

-

Huang et al. 2024. A survey of uncertainty estimation in llms: Theory meets practice. https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.15326 ↩